Neon Williams’ East Somerville shop is full of signage you won’t find anywhere else, but recently a customer brought in something even rarer: a complaint. “He said, hey, this pizza sign you sold me is broken!” Dave Waller, Neon Williams co-owner recalls. He looked over the malfunctioning sign. “I said, I don’t recognize this piece. When did we sell it to you?”

The sign was from 1975. It had been running nearly half a century.

That longevity is a primary selling point of neon. The precisely-bent glass and mechanical induction motors need only occasional maintenance to keep a neon sign running for decades. “People get a bit of sticker shock,” Waller says, but compared to the cheaper alternatives flooding the signage market, these are “long-lasting pieces”.

But the true neon acolytes (a diminished but steadfast bunch) aren’t likely to wax poetic about the age. They’ll tell you about its beauty.

“It’s a quality of light that’s difficult to replicate by other means,” Waller says.

Neon signage creates light by combining a noble gas - often “classic” red-orange neon, vivid violet argon, or pinkish helium—with mercury vapor for intensity, and phosphor or painted-glass coating for a specific hue. This specific alchemy produces a vivid, chemical light uniquely suited to pierce through the rain, fog, and clouds that might dampen or blot out other light sources. Compare the arresting brilliance of the Union Oyster House or Paramount Theater signs downtown with the “false neon” LED that adorns more recently-built cafes or taverns and you’ll see it yourself: there’s no comparison to neon.

This specificity, of course—combined with the relative cheapness of LED—makes neon signage difficult to service. It’s cost-prohibitive for most contracting, building, or marketing companies to keep a neon specialist on staff, which is why Neon Williams is one of the last neon servicing shops in New England.

You’ve probably passed the shop without even realizing it. Since its founding in 1934 as the “Long Life Neon Tube” company, Neon Williams has had many homes, but today it’s beside the East Somerville T stop & Brickbottom Studios. It’s just one in a long row of largely-nondescript warehouses.

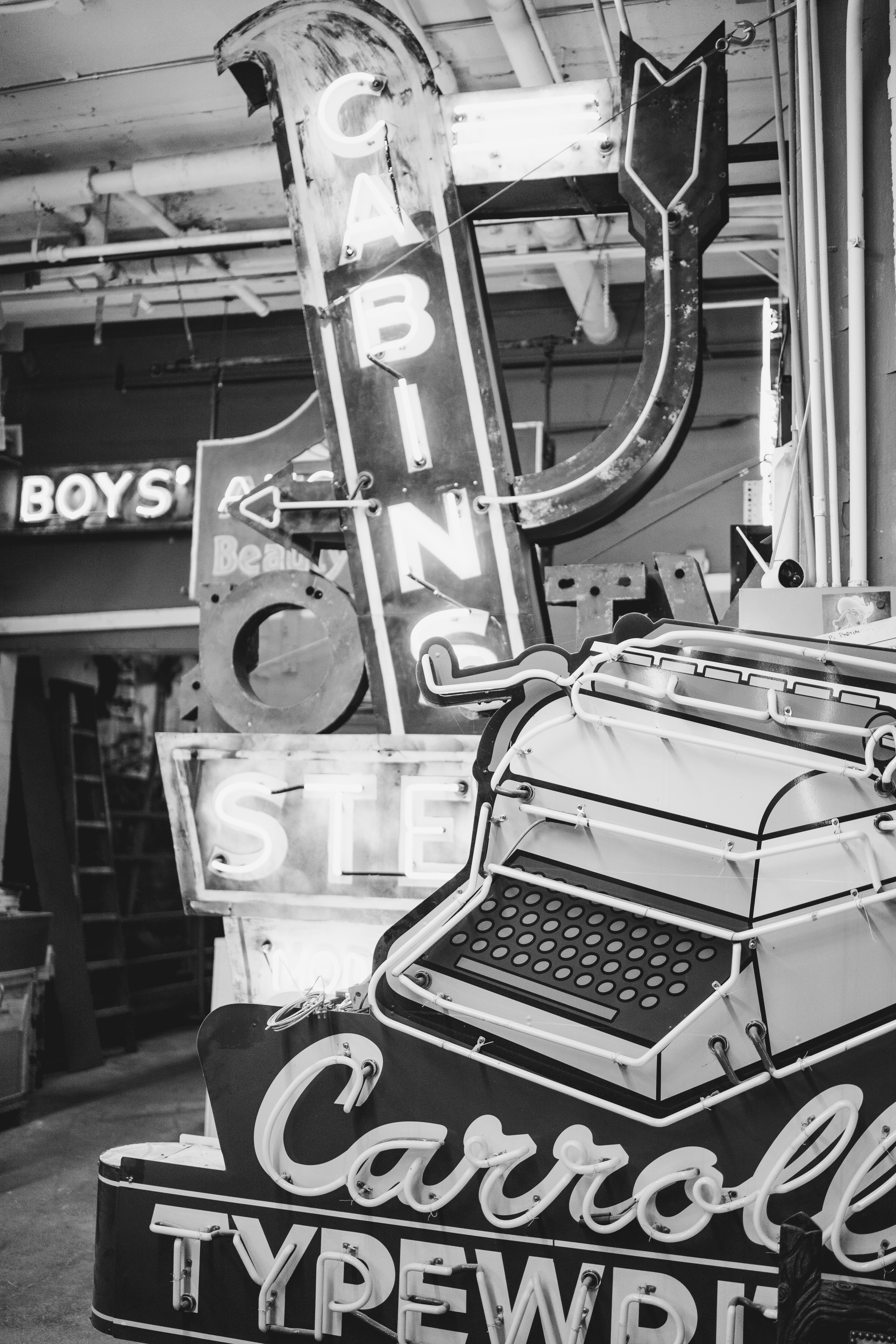

The interior, though, is unforgettable. Ten-foot glowing-red burlesque dancers; a ketchup-dripping hot dog the size of a minibus; hundreds of hand-bent fonts promising long-defunct railroads, hotels, and burger joints. The heat of the glass torches and the mechanical chunk-click of the motorized signs give the impression of a magical factory.

The staff are friendly, welcoming, and love what they do. You’d have to: between the finickiness of the glass tubing, the chemistry of the color production and the heavy-voltage machinery required to blast impurities from the glass tubing, proper signmaking technique can take a decade to develop. Apprentices fizzle out pretty quickly.

Which makes it all the more miraculous that one of the last and healthiest centers of neon expertise is just down the street.

Neon signs were first demonstrated in 1910, in a largely identical way to how it is done today. For the first half of the century, neon signage was so popular that signmaking was an industry of careful technique and closely-guarded trade secrets. This served signmakers well until cheaper and easier-to-install alternatives flooded the market; now, that tendency towards secrecy means that many signs, images, and technique are deeply buried.

What’s been preserved digitally barely scratches the surface of a century of artisanal signmaking. People requesting custom signs from Neon Williams will often go (where else?) to the Internet for design ideas. “The same seven or eight images always float to the surface,” Waller says.

To preserve some of what’s lost, Waller keeps a small library of old neon books, many of them short-run or self-published by individual shops: pictures from neon’s heyday that may never have been digitized.

Waller comes to shop ownership relatively recently. When the eponymous Williams brothers retired in 2019, Dave Waller, his wife Lynn, and their friend Tony took it over.

Prior to that, Waller was simply the shop’s best customer: he’s been collecting neon signs since he was a kid. When he saw a business with a neon sign, he’d patronize them for years, reminding them periodically that if they ever wanted to get rid of their sign, consider him before the town dump.

Waller hastens to clarify that these were, in and of themselves, good businesses. Remember, neon lasts for decades: a local auto shop or restaurant with that kind of longevity must be doing something right

One sign no one was able to save? The old CITGO sign. If you’re new to the city, you may never have seen its neon incarnation. “It’s one of those losses where people don’t even realize what was lost.”

Waller and his staff keep plenty busy with the signs they have managed to save. When we visit, he’s packaging relish and mustard glass drips for a dripping hot dog that by now you should be able to go see in Worcester

Also: they fixed the pizza sign from 1975. But nothing lasts forever, even handcrafted strong neon signs degrade, so the owner might be back. In another fifty years or so. •